Kenilworth Beach Subdivision Development

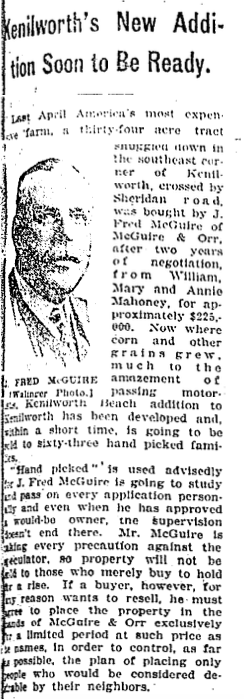

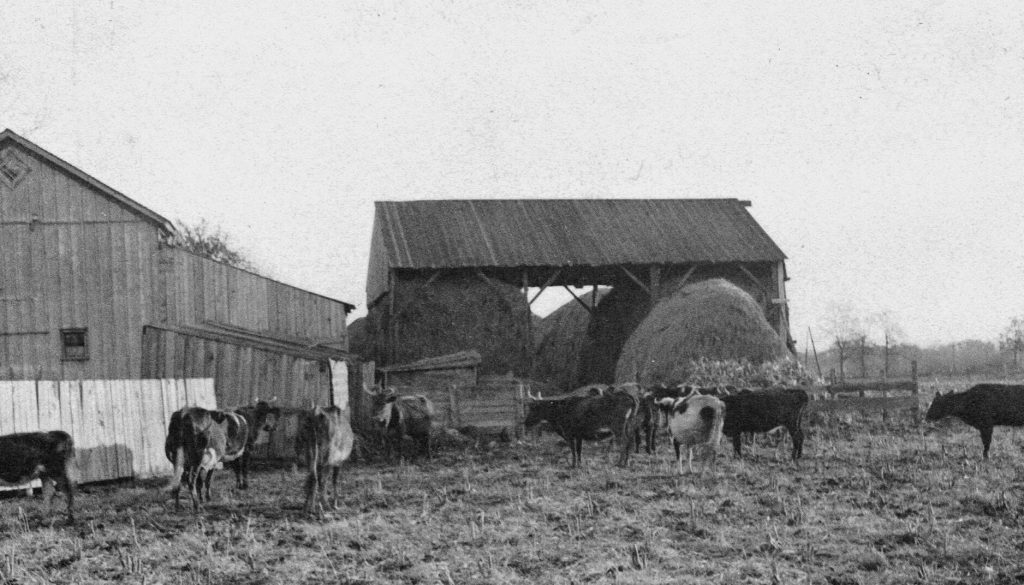

In 1922, after two years of negotiations, Mary and Annie Mahoney – the daughters of Daniel Mahoney – sold their family’s farm to property developer J. Fred McGuire of McGuire & Orr for $225,000.

The sisters, Mary and Annie, kept 8 acres for themselves and sold the remaining 26. At the time of the purchase it was heralded as “America’s most expensive farm”. When Daniel Mahoney first purchased the property in 1855 he only paid $50 per acre. By 1924, it was worth $25,000 per acre.

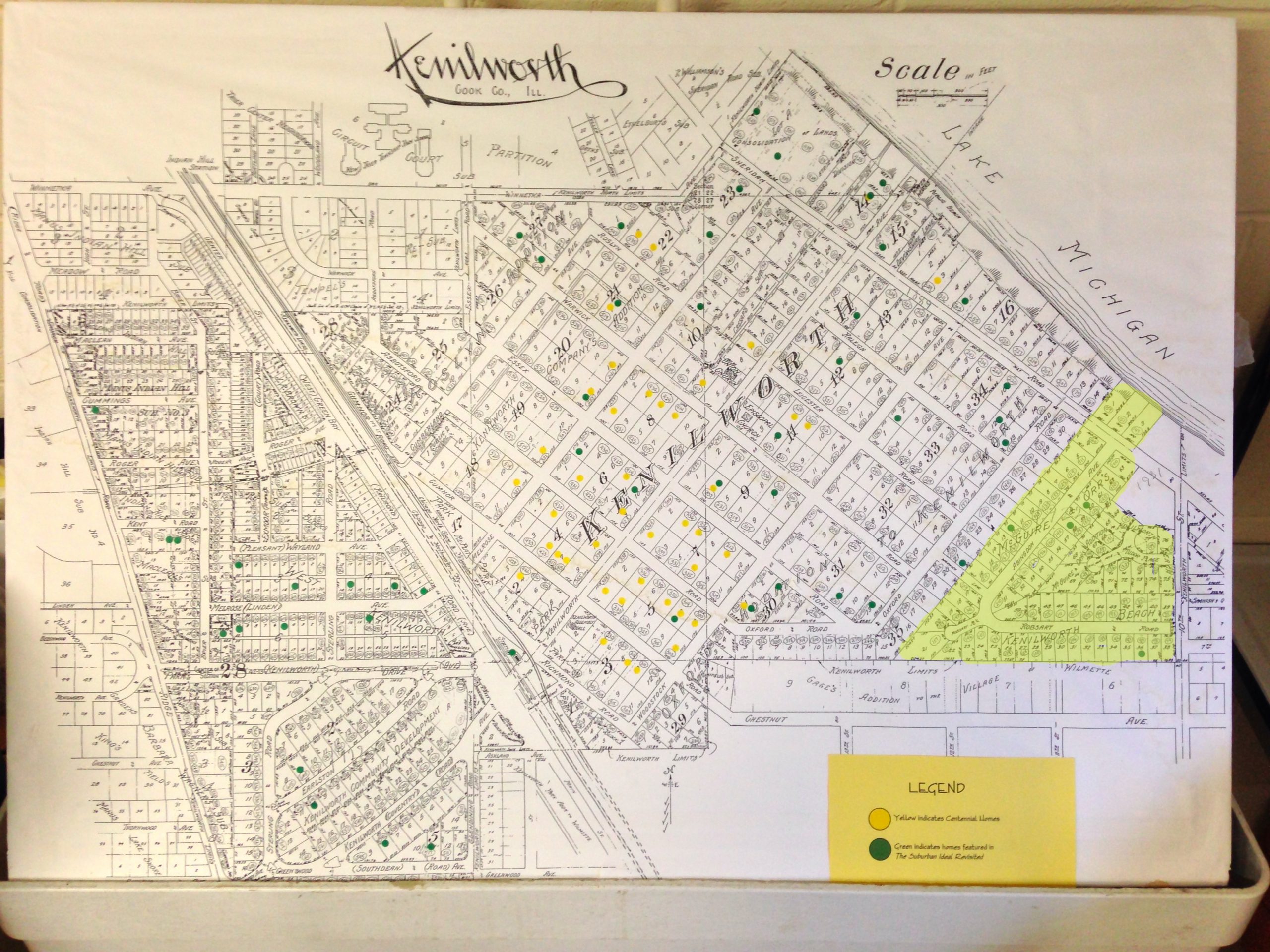

McGuire & Orr developed their purchase into the Kenilworth Beach subdivision which is situated in the southeast Kenilworth along Sheridan Road, Abington Avenue, and Robsart Road. From the 26 acres that made up Kenilworth Beach, McGuire & Orr developed and sold, “sixty-three choice restricted homesites.” McGuire purchased an additional six acres from the Mahoney sisters in 1926, adding 14 homesites along Tudor Place to the Kenilworth Beach subdivision.

When developing Kenilworth Beach, McGuire & Orr included rigid restrictions, including racial restrictions, which followed a trend of the time seen in new subdivision developments across the United States. Before these restrictions were ruled unenforceable by the Supreme Court in 1948’s Shelley v. Kraemer, they were used by subdividers to increase property values and profit from the growing segregative society. Since its inception, the village of Kenilworth has had building restrictions in place via ordinances that restricted the development of hotels, businesses (in certain areas), hospitals, garage placements, specific setback distances from the roads, etc. While there were initially no racial restrictions in Kenilworth, they started to emerge nonetheless once subdividers began buying up property from newly annexed land in the 1920s.

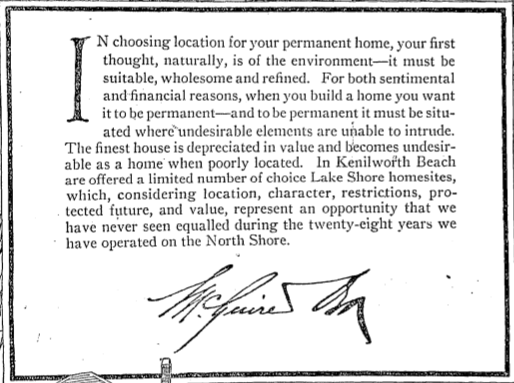

Researching the deeds of various properties in Kenilworth Beach show a difference in restrictions and use of restrictive language, but the advertisements and narrative produced by McGuire and Orr remain consistent, and almost codified. For example, looking at two deeds within the original Kenilworth Beach shows some properties with racial restrictions and some without. The legal language used in the deeds is unapologetically direct, “… said lot shall not nor shall any interest therein be conveyed or leased to or be acquired by any person other than one of the Caucasian race.” Meanwhile the public ads for Kenilworth Beach properties used vague language that could insinuate the use of racial restrictions. Below are a couple examples:

“Property purchased in Kenilworth Beach carries with it absolute assurance of the high character of neighboring home-owners. It is protected by restrictions which guarantee that only homes will be built which are of sufficient value to be in keeping with their surroundings. Wide building lines and perpetual restrictions against business apartment and hotel construction assure the maintenance of Kenilworth as a high class residential community.” October 19, 1922. Chicago Tribune.

“The present addition contains fourteen homesites which will be put on the market June 26. The development of course, will be of a de luxe nature, with ironclad building restrictions. The homes in the first section cost from $22,000 to $45,000 to build.” June 13, 1926. Chicago Tribune.

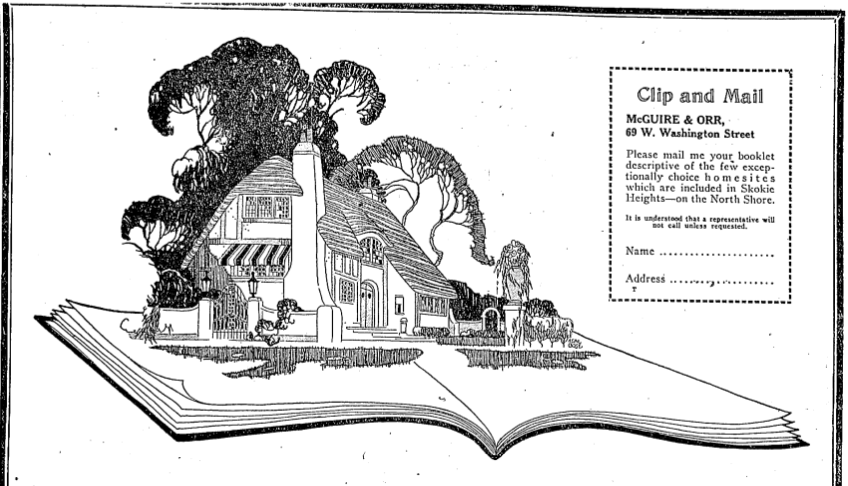

The excerpt from October 19, 1922 refers to the importance and preservation of a specific “character”. Early Kenilworth Company brochures (1890-1914) refer to Kenilworth homes and buildings as having a certain character which was enforced by the use of the building restrictions mentioned earlier (minimum building cost, setback, and use of buildings). However, McGuire & Orr use the term “character” here to refer to the homeowner instead of the homes. Despite deed restrictions becoming a norm for affluent suburban communities, the advertising of racially restrictive property remained subtle, at least was the case with other McGuire & Orr developments, such as Skokie Heights in Glencoe.

McGuire & Orr could afford to advertise their racially restricted properties in a subtle manner because they retained control over who would get to live in their subdivided properties. In an article from 1924, McGuire is quoted as saying, “By providing ironclad permanent restrictions I’ve safeguarded the character of the development, not only to the advantage of present owners but for all time to come.” This tells us that the racial restrictions seen in the deeds were not a product of any Kenilworth official, but rather of McGuire & Orr directly. This is supported by Helen Monchow’s study from 1928, The Use of Deed Restrictions in Subdivision Developments, which showed that most racial restrictions on deeds were added and enforced by subdividers and in rarer circumstances, they were included in city ordinances. We know this wasn’t the case with Kenilworth as there were no such ordinances.

One of the earliest known articles from McGuire’s Kenilworth Beach advertisements mentions that 63 families would be “hand picked” by McGuire himself for the properties. The article explains his process:

“… J. Fred McGuire is going to study and pass on every application personally and even when he has approved a would-be owner, the supervision doesn’t end there. Mr. McGuire is taking every precaution against the speculator, so property will not be sold to those who merely buy to hold for a rise. If a buyer, however, for any reason wants to resell, he must agree to place the property in the hands of McGuire & Orr exclusively for a limited period at such price as the names, in order to control, as far as possible, the plan of placing only people who would be considered deplorable by their neighbors.”

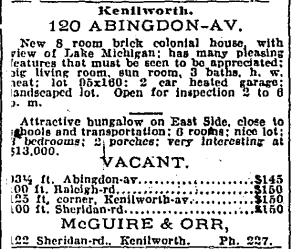

McGuire’s real estate company set up office at 122 Sheridan in Kenilworth (now a part of Mahoney Park) after first purchasing the initial 26 acres in 1922. McGuire was able to retain control over who would be allowed to purchase property in Kenilworth Beach subdivision for as long as their office remained. We have yet to uncover how long McGuire’s influence lasted over Kenilworth Beach subdivision.