The 1934 Liquor Referendum

On December 5, 1933, the 21st Amendment was ratified, repealing the 18th Amendment that prohibited the manufacture, transportation, and sale of intoxicating liquor.

Across the nation, state legislatures enacted new liquor laws in response to the repeal of Prohibition. In Illinois, the Liquor Control Act of 1934 sought to “foster and promote” the regulation of alcoholic liquors. However, the lengthy legislation included certain provisions that drew ire and concern in Kenilworth and nearby villages. One such provision mandated the issuance of a tavern license for any city or village that failed to hold a referendum on the sale of alcohol before May 10, 1934.

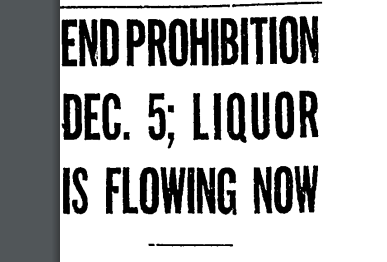

News of this provision quickly spread throughout the North Shore suburbs, where the prospect of saloons and taverns greatly stirred residents wary of such establishments. Decades before Prohibition began in 1919, the North Shore suburbs were “dry,” a term used to describe a municipality that imposed regulations against the sale of alcohol. Many felt that taverns and saloons would hurt the moral fabric and character of their communities. Additionally, the temperance movement – a nineteenth and early twentieth century organized effort to limit or outlaw the consumption and production of alcohol – occupied a strong foothold on the North Shore. Indeed, the sentiment of the temperance movement was reflected in deed restrictions against the sale of intoxicating beverages found during Kenilworth’s early years.

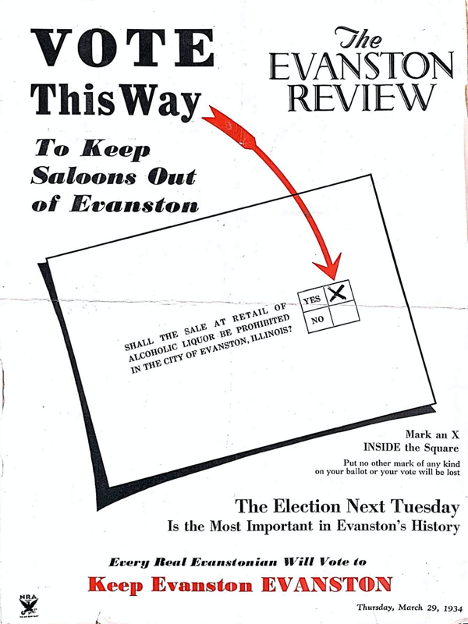

North Shore residents believed that the most effective time to hold a referendum would be during the April elections. To bring a referendum to the ballot, a petition with sufficient signatures (25% of all registered voters) must be filed with the respective Village Clerk no later than March 1, 1934. Given that the Liquor Control Act of 1934 was passed on January 31, residents were left with a limited window of time to circulate petitions. Nonetheless, on February 28, Kenilworth organizers garnered enough signatures to file a petition for a referendum. In fact, two petitions made their way through Kenilworth, demonstrating the popularity of the referendum efforts.

Evanston, Glencoe, Wilmette, and Winnetka also succeeded in securing enough signatures for a referendum. Additionally, residents of unincorporated areas outside of official municipal boundaries in New Trier Township earned the ability to vote on the subject in the upcoming election. These unincorporated areas included the triangle area known today as Plaza Del Lago. Throughout the early twentieth century, “No Man’s Land,” as it was called, developed a negative reputation for its association with illicit activities. Notably, Miralago, a Spanish-styled ballroom built in the 1920s, became a popular destination for gambling and liquor-related activities. It was not out of the imagination then to assume No Man’s Land could be a site of future taverns or saloons. As a result, New Trier Township felt hard-pressed to ensure residents of No Man’s Land provided signatures to permit participation in the referendum.

On April 17, 1934, residents of Kenilworth, and adjoining villages, voted in large majorities in favor of local prohibition of alcoholic liquor licenses. Two-thirds of residents living in unincorporated segments of New Trier Township also voted affirmatively. Thirteen days later, as pursuant with the legislation, Kenilworth and New Trier Township were once again “dry.” Village of Kenilworth officials, cognizant of No Man’s Land’s tendencies, created official maps of the territory to monitor compliance. In July 1934, after reports of the sale of alcoholic liquor and beer in No Man’s Land, the Village Board called on proper enforcement officials to take “immediate steps” to enforce prohibition within No Man’s Land.

Incidents of unlawful and undesirable activities continued to transpire at No Man’s Land throughout the 1930s. In 1942, the unincorporated territory was annexed by Wilmette, after which development projects revitalized the area. In 2017, the Village of Kenilworth voted to end its prohibition of the sale of alcohol, ending its status as one of the last “dry” suburbs of Chicago.

– Will Taylor

Works Cited:

“Liquor Control Act of 1934,” Illinois General Assembly, accessed October 1, 2020, https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/ilcs5.asp?ActID=1404&ChapterID=26#:~:text=This%20Act%20shall%20be%20liberally,manufacture%2C%20sale%2C%20and%20distribution%20of

Shea, Robert. From No Man’s Land to Plaza del Lago (Chicago, IL: American References Publishing Corporation, 1987), 60, 70, 76-85.

Thayer, Kate and Routliffe, Kathy. “Dry no more: Kenilworth, one of last no-liquor holdouts, lifts sales ban,” Chicago Tribune, March 27, 2017. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/ct-kenilworth-liquor-laws-dry-suburb-met-20170326-story.html

Note: Information not directly cited above sourced from Kenilworth Historical Society’s Village of Kenilworth General Reference Collection, Prohibition Referendum, 1933-1934, Folder 3, Box 3.